Images source: Wikimedia Commons, Matt Brim

The October issue of Discovery magazine has an article that piqued my interest, entitled, “This Man Wants to Control the Internet. And you should let him.” The man is Caltech professor, John Doyle, an expert in control theory. His field models dynamic physical systems, which includes things from a mechanical heart to space flight. The key idea is achieving a desired or steady state for one of these systems by taking current information about its state, and “feedback” that information to the system to make adjustments. These feedback system are mathematically modeled. When the system is non-linear and dynamic, for instance a airplane flying through wind currents, the mathematics required become quite sophisticated.

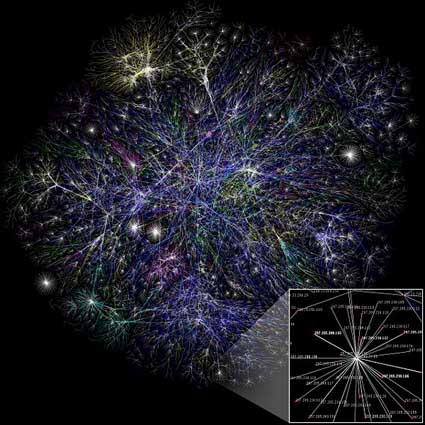

Doyle and his collaborator and fellow CalTech professor, Steven Low, have developed an improved protocol over TCP (or Transmission Control Protocol.) TCP describes how packets of data should be delivered and received over the Internet. FTP, email and WWW applications all rely on TCP. Using control theory, their protocol, FastTCPTM, clocks the time a data packet takes to get to a final destination and make adjustments to optimize its stream of packets. Standard TCP does not take this extra information into account, and relies mostly on a strategy of monitoring lost packets. That is, packets that don’t make it to the finally destination. In the 2006 Supercomputing Network Bandwidth Challenge, they won it with a maximum throughput of 17 gigabits (a full-length movie) per second.

Improvements to the Standard TCP will be important in the coming years, as multimedia services (such as movies on demand) will increase the demand of the current network. Already, VOIP services do not use TCP, because packets sent using TCP cannot be received and sequenced fast enough for real time applications like phone calls.

Doyle and Low, along with Cheng Jin formed the startup, FastSoft, to sell products based on FastTCPTM. However, they have trademarked their name and have submitted patents their technology. This is an important departure from the origins of the Internet, as no one owns that Standard TCP. Having to license or buy FastTCPTM from FastSoft has implications to the future of the Internet, which could lead to its fragmentation.

Last month, at team from Indiana Univeristy, the Technische Universitaet Dresden, Rochester Institute of Technology, Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center won the 2007 challenge. They achieved a peak transfer rate of 18.21 Gigabits/second and a sustained transfer rate of 16.2 Gigabits/second. It is not clear to me what kind of IP, the team from IU has on their technology. However, the received funding from the NSF, which may mean place of some or all of their research into the public domain.

Demands for bandwidth are only increasing. A complete overhaul of TCP is years ago, and involves incremental change, because the network at stake (that is, the Internet) is so important, which Doyle explain the Discover article. How we meet those demands is already controversial.

Susan Crawford notes that Comcast is already traffic shaping bits, by flagging packets by people using BitTorrent. (She also has a nice description of TCP in this post.) Meeting this growing need, the network can improve performance in various ways including: upgrading the infrastructure, such as laying fiber optic cable; improving data compression algorithms, and improving the protocols that control data traffic. In all these areas, the ownership and regulations of these technologies have huge implications on accessibility and adoption of the Internet. Although the Discover article’s title “this man wants to control the Internet” is a play on Doyle’s field of study, it raises an important point. Having public and private protocols may not only make parts of the inaccessible to each other, but further increase bandwidth as another form of economic inequality.

I’ve been slowing making my way through a very good book “Innovation and Incentives,” by Suzanne Scotchmer from UC Berkeley. I’ll close with a quote from her chapter on “Networks and Network Effects”:

“The protocols of the Internet and worldwide web were developed at public expense and put into the public domain. Given what turned out to be at stake, that is probably one of the most fortunate accidents in industrial history.”